Sarah Stone, midwife (letter dated 25 December 1736)

The daughter of a midwife and the mother of a midwife, Sarah Stone was an English woman who practiced midwifery, as she writes, for "five and thirty year," from about the year 1703 until at least 1737.

|

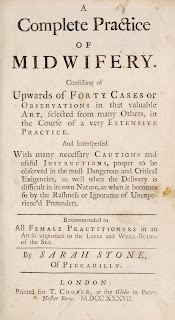

| Sarah Stone, title page, A Complete Practice of Midwifery (1737) |

Almost all that is known about Stone comes from what we can find in her book, A Complete Practice of Midwifery, which was published in 1737. The work seems to represent a culmination of Stone's life's work--intended as a practical guide for midwives, it seems to have been completed just as she was was ending her career.

According to the title page of the book, Stone is living in London with her husband at the time the book appeared: the author of the work is identified on the title page as "Sarah Stone, of Piccadilly." A few pages later, at the end of her preface, she adds that she has been writing "from my house in Piccadilly, over-against the Right Hon[orable] the Earl of Burlington's."

Also included in her preface are details of where she has lived and practiced during her career as a midwife--she began her work in Somersetshire, in Bridgewater and in Taunton, where women's difficult and taxing work in "woolen manufactory" has "been the occasion" of many of the obstetrical difficulties they face. Stone has also practiced in Bristol, where, according to her preface, it has become "quite a fashion" for having a "Man-Midwife," a practice Stone altogether opposes.

Throughout her preface, Stone emphasizes men's lack of preparation for the profession of midwifery. A young man who has taken a course of anatomy as part of his apprenticeship to a barber-surgeon "immediately sets up for a man-midwife," she scoffs--as if "dissecting the dead" has prepared them for caring for living mothers and babies.

For her part, Stone does not think it "amiss" to have "seen dissections and read anatomy," as she herself has done, but a midwife's training is, and must be, more rigorous. She notes that she had been "instructed in midwifery" by her mother and had served an apprenticeship (assisting as her "deputy") for "six full years."

Following her preface, Stone includes a letter written to her husband (referred to only as "Mr. Stone") by "Dr. Allen of Bridgewater," dated 25 December 1736. This letter confirms details about Stone's career, beginning with the doctor's admission that when the couple had "removed from Bristol" and moved to London, he had fears about whether they could succeed there. "You know the only objection I had to your leaving Bristol for London," he writes, "was my fear how you would be able to get an acquaintance in London at your time of life." But, given their "knowledge and skill" in their professions and their "honesty, industry, and care" in their business, he seems convinced that the pair will "surmount" any difficulties they face.

The doctor praises Sarah Stone--according to the account of her career in his letter, she "began her practice" in Bridgewater with "great applause and success." Though she was "then very young," she had been "taught her skill by the famous Mrs. Holmes her mother, the best midwife that I ever knew." Allen adds further that, from Bridgewater, where Sarah Stone had started her practice, she had extended her practice into Taunton, where she "enlarged her experience," before moving on, as noted, to Bristol, which "perfected and fitted her for the Metropolis, London."

Following these introductory materials, Stone turns to her guide. This is no textbook for beginners--rather, A Complete Practice is a series of "observations," that is, more than forty-three case studies through which she illustrates her approach to challenging obstetrical problems.* From her narrative accounts of difficult births, we can fill in a few more details about Sarah Stone's life and practice.

As Stone introduces each case, she notes where the birth that is the subject of each "observation" occurred: a farm in Huntspill (Bridgewater), for example, or the home of a gentlewoman living on Vine Street in Bristol. The range of locations shows how far a single midwife traveled as she was summoned at all hours by women in need.

On rare occasion, a glimpse into her personal life emerges: she is called to attend a farmer's wife in Bromfield, noting that it is just three months after the death of her own mother, who had trained her in midwifery and with whom she practiced--the farmer's woman had been in labor for four days, but the woman's friends had persuaded her, at first, not to call on Sarah Stone because they thought she was still too young to oversee a birth on her own.

In one of the last cases she describes, Stone includes a reference to her daughter, and this allows us to date her daughter's own practice to about the year 1726. According to the account she provides, Stone is faced with a woman in labor who is hemorrhaging. The midwife describes her successful treatment of this poor woman, who "flooded prodigiously." In describing how to treat this condition, Stone notes that her daughter, too, will be able to further spread this information for "the benefit of my sisters in the profession": "having a daughter that has practiced the same art these ten years, with as good a success as myself, I shall leave it in her power to make it known." (Presumably, Stone's published guide will also help in disseminating her successful treatment!)

After the publication of her guide for midwives, Stone disappears from the historical record.

The most detailed study of Sarah Stone remains Isobel Grundy's "Sarah Stone: Englightenment Midwife," in Roy Porter's Medicine in the Englightenment (1995).

Still, with Stone's Complete Practice of Midwifery easily accessible online, you can read about her life and work in her own words for yourself.

*The title page of Stone's Complete Practice indicates that the contents present "upwards of forty cases." Most references to Stone's Complete Practice claim to be more precise and provide the same information--that there are 42 case studies in Stone's manual, perhaps repeating Grundy's reference to "42 observations" (p. 132).

Yet there are 43 numbered observations in Stone's book--43 in the numbered list of contents and 43 in the text. And not every observation presents just one case study--Observations VII, XXI, and XXV, for instance, include two cases each, while the final observation, XLIII, has an interesting structure, moving from Stone's own case to a similar case several years earlier, in which a midwife had been blamed for the death of the mother, several man-midwives blaming that midwife for the loss of her patient. Stone then analyzes what went wrong with that earlier case and offers her own suggestions for how the death of the mother might have been prevented.