Cartimandua, queen of the Brigantes (birth of Emperor Claudius, 19 August 10 BCE)

Cartimandua's name first appears in the Annals of the Roman historian Tacitus: "after seeking the protection of the Brigantian queen Cartimandua," a rebellious British chieftain named Caratacus "was arrested and handed to the victors, in the ninth year from the opening of the war in Britain." Since Claudius had begun his conquest in 43 CE, this would have been about the year 51 or 52. (With few dates for Cartimandua herself, I have posted about the queen of the Brigantes on the birthdate of the Roman emperor.)

|

| Map showing Brigantia, from English Heritage |

The Celtic kingdom of Brigantia included territory that is now centered in Yorkshire. Cartimandua seems to have inherited her role as queen (her grandfather, Bellnorix, had been king of the Brigantes). In his Histories, Tacitus writes that Cartimandua has attained her position because of the "influence of high birth."

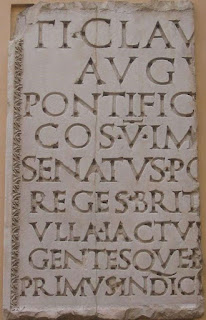

Although it is not known when exactly Cartimandua began to rule in Brigantia, it is widely believed that she was among the eleven Celtic rulers who surrendered to Claudius after his invasion of Britain, a victory commemorated in the now-lost Arch of Claudius.

In his account of Cartimandua in the Annals, Tacitus indicates that the queen was married, her husband a man named Venutius. Although Tacitus may have written more about the origins of Venutius--in his first reference to him, Tacitus refers to the fact that he had "mentioned earlier" Venutius's "Brigantian extraction"--this part of the Annals does not survive. In noting Cartimandua's marriage, historian Nicki Howarth makes it clear that "any claim Venutius made to sovereignty was subordinate to that of his wife." Cartimandua "was the queen and not a consort," and that if her marriage to Venutius was a "dynastic" alliance, either "she came from the more powerful of the two [families]" or "she had succeeded an existing ruler."

Tacitus focuses on two key events in Cartimandua's reign: her handing over of Caratacus, a rebellious British chieftain, to the Romans (mentioned above, in the first quotation from Tacitus), and her ongoing disputes with Venutius, whom she divorces and who rebels against her several times.

In the first case, Queen Cartimandua is rewarded for her loyalty to Rome, receiving support on several occasions from rebellious subjects, notably in 48 CE, when "Roman forces intervened for the first time to help her quell these disturbances." In Tacitus's words, Cartimandua "received the protection of the Roman arms." And so, in 51 CE, when a rebellious British chieftain named Caratacus was defeated by the Romans and took refuge in Brigantia, Cartimandua did not offer him shelter, much less support. Instead, according to Tacitus, she "handed him over to the victors [the Romans who had defeated him]."

|

| Fragment from the lost arch of Claudius "describing the surrender of 11 native rulers," a number that likely included Cartimandua |

In turning over Caratacus, Cartimandua was thus loyal to Rome. But the judgment of Tacitus here is noteworthy. Instead of praising the loyal Brigantian queen, he condemns her--Tacitus regards her treatment of Caracatus as an act of "treachery," and he adds that the rewards heaped on her by the Romans for her act--increased power and wealth--were the source of a "wanton spirit which success breeds."

In recounting the episode of Caratacus, Tacitus offers no praise for Cartimandua's loyalty to Rome, nor does he provide her with any opportunity to explain the reasons for her actions.

By contrast, he offers a sympathetic picture of the rebellious Caratacus. "Even in Rome," Tacitus writes, "the name of Caratacus was not without honour." And the emperor, by holding a triumph to display the captive Caratacus and his family in chains, has misjudged: "by attempting to heighten his own credit, [Claudius] added distinction to the vanquished."

And then, while he gives no voice to Cartimandua, Tacitus puts an extended, noble speech into the mouth of the defeated Caratacus. It is so noble and so persuasive that the rebel and his family members are all pardoned, and they live happily ever after in Rome.

Meanwhile, back in Britain, it's now the turn of Venutius to act up. In this second episode in the life of Cartimandua, Tacitus focuses on Venutius's repeated acts of rebellion against his wife (and the power of Rome). In the years 51 CE and 57 CE, Venutius twice attempts to overthrow Cartimandua and, by extension, Rome. In 51 CE, his rebellion is put down by Roman troops, who defend the queen of the Brigantians. Notably and oddly, as Tacitus describes the rebellion of Venutius in his Histories, Venutius is not condemned for his actions. Rather, Tacitus says that he was inspired not only by "his natural spirit and hatred of the Roman name" (?) but also "by his personal resentment toward Queen Cartimandua."

While the pair are reconciled in 51 CE, Cartimandua and her husband separate permanently after his second rebellion against the queen six years later, this one also put down with the assistance of her Roman allies. Finally, in 69 CE, Venutius rebels a third time. In his description of events, Tacitus attributes the break to Cartimandua's lust. According to Tacitus, "She grew to despise her husband Venutius, and took as her consort his squire Vellocatus, whom she admitted to share the throne with her. Her house was at once shaken by this scandalous act."

The opposition between Venutius and Vellocatus is, in the view of Tacitus, stark: "Her husband was favoured by the sentiments of all the citizens; the adulterer was supported by the queen's passion for him and by her savage spirit." But what began as opposition to Queen Cartimandua did not end there--Venutius "extended his hostility to ourselves," writes the Roman historian.

In her more nuanced analysis of the characterizations of Cartimandua and her relationship with Vellocatus, Howarth notes that some modern historians, following Tacitus, have described their alliance as an "affair" or as "adultery." Having taken a former "squire" to share her throne is regarded not only as a scandal but a source of shame. Tacitus also seems to attribute the separation of Cartimandua and her husband to a kind of nobility of action on the part of Venutius. Tacitus suggests that he had only allied himself with Rome because of his wife: "He had long been loyal, and had received the protection of the Roman arms during his married life with Queen Cartimandua: then had come a divorce, followed by immediate war, and he had extended his hostility to ourselves" (Annals).

In her analysis of events, Howarth untangles the chronology of events in Cartimandua's life, a chronology that is confused in Tacitus's accounts. Howarth points out that Cartimandua's difficulties with Venutius had begun by the year 51 CE, and that the couple had divorced in 57 CE, a dozen years before the queen's relationship with Vellocatus in 69 CE. The queen was "perfectly at liberty" to make Vellocatus her consort "without committing any sort of infidelity." And while Vellocatus may originally have been an "armour bearer" for Venutius, Howarth notes that this is not an indication of any servile status (if it were, Tacitus would have made that clear, noting it as part of Cartimandua's scandal and shame). As Venutius's "squire," Vellocatus would have been a member of the Brigantian elite, and after careful analysis of what can be known about him, Howarth explores the possibility that he might even have been of Roman origin.

Historian Andrew Roberts suggests that the separation between Cartimandua and Venutius in 69 CE was likely not caused by the queen's lust but by "the internal politics of the Brigantes" that "led to differing views on policy, leadership and the Roman alliance." The death of the Emperor Nero, in 68 CE, followed by the uncertainties of "the year of four emperors," in 69 CE, offered Venutius yet another opportunity for rebellion.

Having elided events in Cartimandua's life and reign, Tacitus portrays the rebellion of Venutius in 69 CE in gendered terms. In defending herself, Cartimandua seized members of Venutius's family: "Cartimandua adroitly entrapped the brother and family connections of Venutius." Instead of offering support for what seems to be a reasonable act under the circumstances, or instead of offering "Cartimandua's" view of this decision, Tacitus focuses on the reaction of Venutius: he is, in Tacitus's view, "[i]ncensed at her act, and smarting at the ignominious prospect of submitting to the sway of a woman."

When Venutius invaded Brigantia, Cartimandua once more appealed to her Roman allies for aid. But given the unsettled affairs in Rome, sufficient troops were not available. Cartimandua was "rescu[ed] from danger" by Roman troops and fled to the Roman fort at Chester.

|

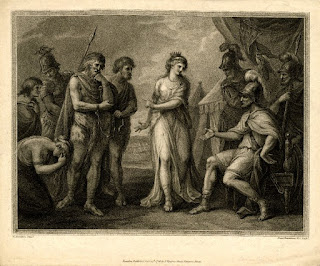

| Francesco Bartolozzi's imagined delivery by Cartimandua (center) of Caratacus to a Roman general; Bartolozzai's eighteenth-century print was first published by Susanna Vivares (fl. 1781-97) |

Venutius ruled briefly in Brigantia after he forced out Queen Cartimandua, but by 71 CE, under Vespasian, Romans had, in the words of Tacitus, a "more cheerful conclusion." Venutius was defeated, and Brigantia brought fully under Roman rule.

What happened to Cartimandua after she arrived at the Roman fort is not known. Nothing more is known about her.

It's interesting to note here that, while the story of Cartimandua's contemporary, Boudica, is widely known today--there's even a sculpture in London--Cartimandua's is much less well known, despite the fact that she ruled successfully in Brigantia, under the most difficult of circumstances, for more than twenty years . . . Tacitus also provides an account of Boudica, her rebellion, and her defeat. Whether an ally of the empire or a rebel against the empire, a woman is not bound to a happy ending.

In addition to Howarth's Cartimandia, Queen of the Brigantes, I recommend David Braund's account of Cartimandia in his Ruling Roman Britain: Kings, Queens, Governors and Emperors from Julius Caesar to Agricola.