|

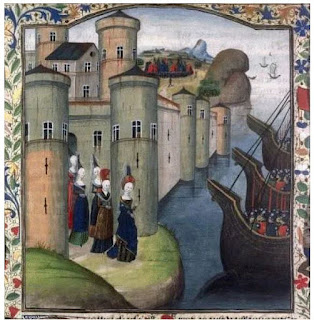

Jeanne of Flanders and her husband,

entering Nantes in 1341,

an illustration from Jean Froissart's

Chroniques (BnF 2643, fol. 87r) |

In a ceremony performed at Cathédrale de Notre Dame de Chartres on 14 May 1329, in the presence of the French king (now Philip VI, who began his reign in 1328), Joanna of Flanders was married to John de Montfort, the son of Arthur II, duke of Brittany, and his second wife, Yolande of Dreux. (As an interesting note: Yolande's first husband had been Alexander III of Scotland, so for the eight months she was married before he died, she had been queen of Scotland.)

Joanna's new husband inherited his title, count of Montfort-l'Amaury, from his mother, and his marriage to Joanna seems to have been a way to improve his financial and political situation--she was the sister of the count of Flanders, and her brother had promised John de Montfort a considerable dowry from the counties of Nevers and Rethel. (For the details of the ceremony and this dowry, click

here.)

But the dowry Joanna's brother promised was not paid, and the legal wrangling over the count of Flanders's failure to pay his sister's dowry would last for more than three decades, eventually outlasting all of them--Joanna, her husband, and her brother.

John de Montfort's dispute with Flanders over his wife's unpaid dowry was a decade old by time Joanna gave birth to her first child, a son, named John, in 1339. A second child, this time a daughter, Joan, was born in 1341.

It was at this point that the couple was plunged into yet another family conflict, now about John de Montfort's inheritance--or potential inheritance--from his father. After the death of Arthur II in 1312, he had been succeeded by his eldest son, John de Montfort's half brother who, confusingly, was also named John. But despite having been married three times, John III, duke of Brittany, died childless on 30 April 1341--and, as historian Sabine Baring-Gould

writes, "No sooner was he dead than an explosion ensued."

John III had hated his father's second wife (John de Montfort's mother) and had spent many years trying to have his father's second marriage posthumously annulled and his half siblings rendered illegitimate. His preferred heir was

Jeanne de Penthièvre, his niece, the daughter of his younger brother, Guy, who had died in 1331.

But the "rights" to succession in Brittany at the time of John III's death were unclear.

The question was whose

claim took precedence? Arthur II of Brittany had had three sons by his first wife, but when John III died, the only surviving heir was Guy's daughter, Jeanne de Penthièvre. Yet Arthur II of Brittany had had another son, John de Montfort, by his second wife, as we have seen. So, could a daughter--in this case, Guy's daughter--inherit her father's rights of succession? That is, did John III's younger brother, Guy, have a right of succession that could be passed to his daughter, Jeanne de Penthièvre? Or did the succession belong to the next eldest male heir in the line? That is, did John de Montfort, as the only surviving son of Arthur II, have a right of succession? With John III leaving no direct male heir, who has the better claim: his half brother or his niece?

The War of the Breton succession, 1341 to 1365, was fought to resolve this question. It became part of a larger conflict, the Hundred Years' War, which also involved rival claimants to an inheritance, in this case the French throne. The rival claimants to the duchy of Brittany were supported by the king of England and the king of France, interested parties in the succession in Brittany. But the claimants they supported in Brittany were at odds with the claims they made in their own dispute over the legitimate succession to the French crown, one of the issues that had precipitated the conflict now known as the Hundred Years' War.

So: the king of England, Edward III, made his claim to the French throne through a female line--but he supported John de Montfort when it came to who should inherit Brittany. And the king of France, Philip VI, who had come to the throne by putting aside the claims of a daughter in favor of those of a younger son--well, he supported Jeanne de Penthièvre.* (For all of this, see Jean-Pierre Leguay and Hervé Martin's

Fastes et malheurs de la Bretagne ducale 1213–1532; click

here.)

Further complicating an already complicated situation, John de Montfort's grandmother, Beatrice of England, was the daughter of King Henry III of England, making John de Montfort and Edward III cousins. And as for Jeanne de Penthièvre's husband--the mother of Charles of Blois was, as we have seen, Margaret of Valois, the French king's sister.

All of this is an incredibly long and complicated background to the events of 1341, when Jeanne, or Joanna, of Flanders, became Jeanne, or Joanna, la flamme, "the fire." What transformed her, catapulting her from relative obscurity to notoriety?

At first, John de Montfort's in Brittany succession seemed assured, and the couple entered Nantes, the capital of the duchy, in 1341. As the chronicler Jean Froissart

writes, "he was received as their lord, as being the next relation to the duke just departed." Summoning "all the barons and nobles of Brittany" and the "councils of the great towns," John de Montfort invited them to "do their fealty and homage" to him "as their true lord." And, according to Froissart, "it was done." For good measure, Montfort seized the treasury at Limoges.

To secure his title, Montfort

moved quickly: "by violent or gentle means," he aimed to "subdue his enemies." He took Brest, Arras, and Rennes before moving on to the town of Hennebont, where he was advised that he could lay seige to the castle "a whole year" and still not take it "by dint of force"--and so he captured it by means of a ruse, at least according to the version of the story that Froissart tells. Although modern historians have noted that Froissart's geography and chronology are confused, Montfort did take control in Brittany. Or most of it.

|

"Jeanne la Flamme" defending her castle,

illumination from Jean Froissart's Les Croniques.

((BnF 2663, fol. 87v)

|

Because not all of Brittany had accepted John de Montfort's claim to the title, and while Montfort sought help from Edward III to enforce his claim, at this point being awarded the title earl of Richmond, Charles of Blois appealed his claim to Brittany, in the right of his wife, to Philip VI, to whom he paid homage.

In August 1341, the two claimants appeared before the parliament of France to make their case--on 7 September, a decision was rendered in favor of Chales of Blois. But by the time the judgement was issued, John de Montfort had fled back to Brittany.

By September of 1341, Charles of Blois had amassed a large army; in October, he laid seige to a chateau at Champtoceaux. Attempting to come overcome Charles and his besieging forces, John de Montfort was defeated. He fled to Nantes, but he was forced to surrender

after fifteen days, on 2 November. In December, he was taken to Paris under safe conduct, but when he refused to give up his claims to Brittany, he was imprisoned in the Louvre.

Rather than accepting her husband's defeat, Joanna of Flanders assumed the title duchess of Brittany and resumed the fight--she sent for assistance to Edward III in England, and according to the chronicler Jean le Bel, she

suggested a marriage between her son and one of the the English king's daughters. Meanwhile, she began preparing to defend herself--and Brittany.

Charles of Blois captured Rennes in May 1342 and began his march to Hennebont, where Joanna had withdrawn, preparing for the castle's defense. The chronicler Jean le Bel

described her actions during the fight: “the valiant countess was armed and rode a great courser from street to street," and while she rode, she was "summoning everyone" to defend the city. Nor was she the only woman to act--she commanded "all the women of the town," regardless of class, to "carry stones and pots full of quicklime to the walls and throw them at their attackers."

And then, "mounting the towers" and surveying the battle below, "the valiant countess" once again mounted her horse; now "fully armed," she led three hundred men at arms straight into the enemy's camp, where they killed the defenders that had been left behind as guards and set everything on fire.

Seeing no way to safely re-enter the castle, Joanna of Flanders took off, riding to her castle of Brayt, where she was well received. Meanwhile, the besiegers mocked the inhabitants of Hennebont, telling them that their countess was lost and that they wouldn't see her (if my translastion is correct, they

actually say that they won't see her again in one piece).

But the besieged inhabitants of Hennebont did see their "valiant countess" again--just

five days later, she was back, accompanied by a well-armed force. She managed to re-enter the city, her return saluted by trumpets, drums, "and other instruments."

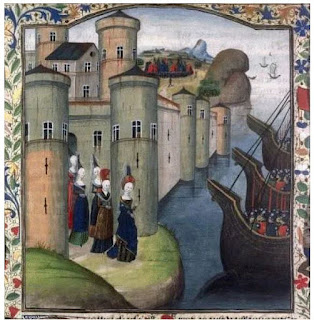

After her triumphant return, the situation becomes more dire. "Twelve great siege engines" were brought to lay waste to the city and the castle, and the defenders began to waver in their resistance. The "valiant countess," however, did not lose heart. She encouraged the town's defenders, "praying, on the honor of Our Lady," that they not do anything rash, asserting her own certainty that help would arrive within three days.

The suffering inhabitants of the besieged city were not so sure. Just as they were about to surrender, submitting themselves to the besieging forces of Charles of Blois, Joanna looked "from out of the castle's windows." "I see the relief that I have coming that I have for so long desired," she

cried out. It was an English fleet, sent by Edward III to her aid, arriving in August 1342.

|

Joanna of Flanders greets the fleet

sent from Edward III to Hennebont;

image from Jean de Wavrin's fifteenth-century

Anciennes chroniques d'Angleterre

(BnF 76, fol. 61r)

|

Still, the War of the Breton Succession continued. During a period of truce, Joanna of Flanders traveled to England, seeking additional aid from Edward III. He provided her with men of arms and archers, but while returning to Brittany, the English ships--with the "valiant countess" on board one of them--were attacked by allies of Charles of Blois. Joanna of Flanders fought back. As Froissart wrote, she had "the courage of a man and the heart of a lion"; "equal to a man,"

she "combated bravely" with "a rusty sharp sword in her hand." (Although modern historians have questioned whether this sea battle ever occurred, Sarpy

writes that, "because of the greatness of Joan of Flanders it was not out of the realm of possibility.")

On landing, her forces re-took Vannes, put the city of Rennes under siege, and attempted the relief of Hennebont. But with the English fighters now in Brittany, Joanna of Flanders's remarkable military leadership was done.

Ater the death of Charles of Blois, the claims of Joan of Penthièvre to Brittany collapsed, and with neither the French nor the English able to secure a military victory, a truce was concluded. John de Montfort became duke of Brittany. He was finally released from his imprisonment, and seemed to have been under a kind of house arrest. But he escaped to England, paid homage to Edward III, and placed his children's guardianship in the Englisn king's hands on 20 May 1345. He returned to Brittany but died at Hennebont just months later, on 26 September 1345.

Joanna of Flanders, meanwhile, had been removed from the picture. After finalizing the truce with France on 19 January 1343, Edward III had sailed back to England a month later, on 22 February. When he left, he took with him Joanna of Flanders and her two children.

The crossing was difficult, the king's ship arriving on 2 March. Once in England, Joanna of Flanders was "

abruptly moved" to Tickhill Castle in south Yorkshire in October 1343 by the king's order. Her children, meanwhile, were removed from her custody in August, ultimately placed into the care of the king's wife,

Philippa of Hainault.

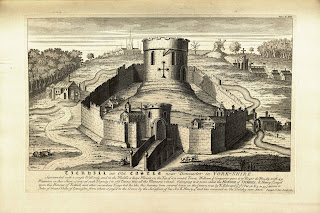

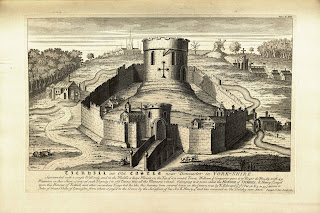

|

A sixteenth-century print of Tickhill Castle,

where Joanna of Flanders spent decades |

What had happened to Joanna of Flanders? Why was she made to disappear? Indeed, she remained largely out of sight for the next thirty years, under the guardianship of one man or another, until her death.

The answer has largely been that she went mad--a false narrative that, as we have seen in many entries in this blog, is a commonplace excuse.. "She's just crazy" has always been a way to eliminate an inconvenient woman. (The most

well-known example of this is Juana of Castile, "la loca," but insanity is

just one way to get rid of royal and aristocratic women.)

Even in the twentieth century, Edward III's biographers have been content with this explanation--in his 1983

King Edward III, Michael Packe

declares that Joanna's "recent energies had swamped her reason." Thirty years later, Ian Mortimer made the same

slighting reference to the fate of Joanna of Flanders: Montfort's "lion-hearted wife had gone mad," he says (

The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation). In

Edward III (2011), W. M. Ormrod is less explicit but seems to come to a similar conclusion,

indicating that Joanna of Flanders's lived out the rest of her life "in the obscurity of various provincial royal castles" having been "exhausted by her efforts on behalf of her absent husband."

But as Julie Sarpy argues, first in her 2016

Ph.D. dissertation, "Keeping Rapunzel: The Mysterious Guardianship of Joan of Flanders the Case for Feudal Constraint [sic]" and in

her 2019 Joanna of Flanders: Heroine and Exile, origins of the story of her madness can be traced to a nineteenth-century historian, Arthur Le Moyne de La Borderie, and his massive three-volume

Histoire de Bretagne. With no contemporary evidence to support his conclusion, he nevertheless proclaimed, “. . . Jeanne de Flandre était devenue folle!”

And so it all began. As Sarpy documents in great detail, there is no evidence at all for the madness of Joanna of Flanders.

Painstakingly examining all the contemporary records, Sarpy finds that, as late as 1346, Joanna of Flanders was still accounting for her expenses, and she still retained her household. But it is also clear that she was being held in Tickhill "under order"

and that her "guardianship was an unlawful action by a king seeking willfully to detain her." Her liberty was "a liability" for him--Edward III "needed her out of the way, and as he was king, no

one challenged him."

The English king's motives were financial--control of the finances of Richmond, for example--as well as political and military, part of

his "broader foreign policy aims" in France. Rather than having succumbed to madness, Joanna of Flanders was a political prisoner. (Edward III's father, Edward II, and his grandfather, Edward III, had both gotten rid of dangerous women by imprisoning them--click

here and scroll down.)

While the circumstances of her life at Tickhill seem to have been comfortable enough, befitting her status, Joanna did

attempt to "escape" in 1347, though whether she left Tickhill willingly or was abducted isn't clear--she was captured and returned. She was ultimately moved to Chester Castle, where on 16 July 1360, she met with her son, John, now duke of Brittany--it was the first time the two had seen one another for seventeen years. They made a pilgrimage to Walsingham the following summer.

She seems to have been returned to Tickhill Castle, but by 1371, she was being held in High Peak Castle (Derbyshire).

She is last mentioned in official records on 14 February 1374, when a payment was made to her custodian. Since no other reference is made to her--and no more payments were recorded on her behalf—she likely died soon thereafter. She would have been in her late seventies.

Joanna's son eventually succeeded as John IV, duke of Brittany, first as a minor under the control of Edward III but after 1364, in his own right. He struggled to break free of English influence, however, at one point even forced into exile in England, but for the last decade of his life, he ruled in peace (he died in 1399). He was married in 1361 to Mary of England, Edward III's daughter, but she died just months after their marriage. He was then married to another English bride, Joan Holland, in 1366, but the two had no children before her death in 1384. John's third wife was Joan of Navarre, whom he married in 1386--the couple had a whole bunch of children, including John (b. 1389), who succeeded his father as John V, duke of Brittany, and Arthur, who succeeded two nephews, sons of his elder brother John, as duke of Brittany. (As Arthur III, he was duke from September 1457 to December 1458.) And, by the way, Joan of Navarre, duchess of Brittany, widowed in 1389, became queen of England in 1403 when she married King Henry IV.

As for Joanna's daughter, Joan, she remained in England. She married Ralph Basset, third baron Basset of Drayton c. 1380, when she was thirty-nine years old, and she was widowed in 1390. She died on 8 November 1402.

*When Philip IV of France died in 1314, he was followed on the throne by his son, Louis X. When Louis died in 1316, he was survived by a four-year-old daughter, Joan--a son, born posthumously, lived only five days. Rather than Louis' daughter, his brother Philip became king of France as Philip V. In his turn, Philip V had four daughters but no sons--when he died in 1322, his younger brother, Charles, succeeded him. When Charles IV died in 1328, he had one daughter, but no son--a posthumous child was also a girl. And so Charles IV was succeeded on the throne by the son of the younger brother of Philip IV, who became Philip VI.

For his part, Edward III of England claimed to the French throne through his mother,

Isabella of France--she was the youngest surviving child of King Philip IV.