Florence B. Loftus, First Female U.S. Customs Inspector in Seattle, Washington

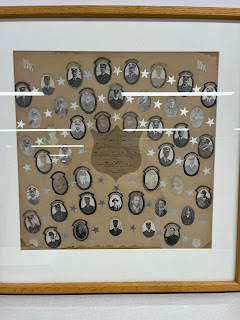

A few weeks ago, my son sent me a series of texts. "Soooo," he began. "This was unearthed. All the customs inspectors in Seattle 1904-1913."

The "this" he referred to was plaque containing dozens of small photographs. But before I could find my glasses so I could see exactly what he'd sent, there was a second text: "Everybody has a name BUT ONE."

As you might be able to guess from the title of this post, the "ONE" unnamed portrait on the plaque was the lone woman in the group. All the other photos were neatly labeled with the names of the pictured men. The woman, by contrast, was identified only by her job title, "Inspectress."

|

| The unidentified female customs inspector, the only inspector without a name |

Of course my son was pretty sure of what would happen next. I had to find out who this unnamed "inspectress" was. He knows exactly how to push my buttons.

My son is a supervisory officer for U.S. Customs, working at the Port of Seattle. He and his colleagues had somehow come across a wood-framed, star-spangled plaque with a shield in the middle identifying the group pictured on it: "Customs Inspectors Stationed at the Port of Seattle, 1904-1913."

Carefully arranged around the central shield and among the silver stars were 45 separate photographs, each one of a customs inspector. Most were identified by their initials and last name: "S. T. Boardman," "R. L. Ballinger," and "J. A. Hock," for example. A few had their first names in addition to their surnames: "Moses Knox," "Perry Stiffler," and "Harry Lehr," among them. One guy's name was abbreviated: "Thos. Jarrett."

But there was that one, crucial exception. It takes a minute to find the single woman in this crowd--the photo of the "inspectress" is just below the point of the shield.

|

| The plaque identifying 44 (of 45) "Customs Inspectors Stationed at the Port of Seattle, 1904-1913" |

And just like that, I was hooked. I still hadn't finished my morning coffee by the time I found Kit Oldham and Peter Blecha's Rising Tides and Tailwinds: The Story of the Port of Seattle 1911–2011 (Port of Seattle, 2011 [to access, click here) as well as Padraic Burke's earlier A History of the Port of Seattle (Port of Seattle, 1976, click here to preview and search inside). They were fascinating histories, but not really about the Customs Office operating out of the port.

There were a few interesting references to the operations of the Customs Service in Clarence Bagley's two-volume History of Seattle from the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time (1916), although I admit I got a sidetracked by the first sentence of the second volume: "The opportunity to prove that Seattle was established on a foundation of law and order, that it was not a child of every passing whim or prejudice, came early in 1896 when the Anti-Chinese craze reached its boundaries."

Once I got myself back on track, I realized that Bagley's book didn't have the kind of information I was looking for either. Turning to an online search, I found the U.S. Customs and Border Protection website--there, in a section under "History," is a question: "Did You Know?" I certainly did not know that in 1927 Anna C. M. Tillinghast was appointed as a district commissioner of immigration (for Boston), becoming "the first woman appointed to this position in the Department of Labor's Bureau of Immigration." But I know now. (For a biographical sketch of Tillinghast at the USCBP website, click here.*)

At the website of the National U.S. Customs Museum Foundation, I learned that, in 1829, a woman named Elizabeth Kelly worked as a nurse at the Customhouse in New Orleans and that "she may have been first female employed by Customs."**

And I discovered that, after the Civil War, the U.S. Congress passed an "Act Further to Prevent Smuggling and for Other Purposes," providing for the hiring of female customs inspectors, whose duties were the "examination and search" of women, presumably those suspected of some sort of customs violation. (I even tracked down the act--39th U.S. Congress, Session 1, Chapter 201, 18 July 1866: "the Secretary of the Treasury may from time to time prescribe regulations for the search of persons and baggage, and for the employment of female inspectors for the examination and search of persons of their own sex.")

While I was at the Customs Museum website, I also learned that 1874 was the first time "badges" were used for inspectors "on special service," that is, “District Inspectors. Boarding Inspectors, Coast Inspectors, Frontier Inspectors, Night Inspectors, Female Inspectors [emphasis added], Discharge Inspectors and Special Inspectors."

As fascinating as all this was, it wasn't getting me any closer to finding the identity of the unnamed female inspector working at the port of Seattle between 1904 and 1913. My next move was to head to the digital archives for Seattle's two major newspapers at the time, the Seattle Daily Times (now the Seattle Times) and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, both of which are made available online through the Seattle Public Library.

But before I could begin (not that I knew how I could find the unnamed woman, aside from trawling through decades of newspapers), I got yet another text from my son, this one including yet another photo. And just like that, there she was, with her name, Florence Loftus:

This photo of a photo came from one of my son's colleagues, a man very interested in the history of the Customs Service in Seattle, the image he captured appearing in a United States Customs Service publication by Harvey Steele, Northern Approaches: The United States Customs Service in Washington, 1851-1997 (1998).

As it turns out, Florence's husband, Chief Inspector Frank P. Loftus, was, in Steele's words, "one of the truly legendary figures in the history of U.S. Customs of Washington," and there is an entire section of Northern Approaches dedicated to his career. The only mention of Florence's career, by contrast, is in the caption to this photo (above): taking up her position in 1909, she "discharg[ed] her duties with, in the words of a press account at the time, 'as clear an eye . . . as any of the uniformed men who work beside her.'"

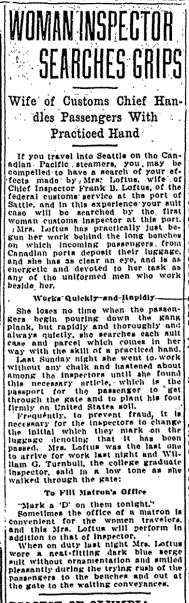

Having found her name, I could search for Inspector Florence Loftus in the Seattle newspapers. While there were scores of articles chronicling the daring escapades of Chief Inspector Loftus throughout the many decades of his service, I could find very little about Florence's activities. The first reference is from an article in the 29 May 1911 edition of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, "Woman Inspector Searches Grips."

|

| Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 29 May 1911, p. 8 |

This piece does mention her status as the wife of Frank Loftus, but it also shows a competent professional woman performing her job. Noting that she is the "first woman customs inspector at this [Seattle's] port," the article adds that she is an experienced inspector, performing her work with a "practiced hand."

This is the news story from which Steele has drawn his brief description of Florence. She has "as clear an eye" as her male colleagues, but the description omitted by Steele's ellipses (above) notes that she is "as energetic and devoted to her task" as the men with whom she works.

Florence Loftus dispatches her duties "rapidly," "thoroughly," and "quietly." I also love the description of her professional attire: "a neat-fitting dark blue serge suit without ornamentation."

The article mentions that she sometimes acts as "matron" for female travelers. I am not quite sure what the role of "matron" would entail, though the article suggests that, in addition to her other duties, she offered assistance of some sort: "Sometimes the office of a matron is convenient for the women travelers, and this Mrs. Loftus will perform in addition to that of inspector."

A second article appears in the Seattle Daily Times, dated 20 February 1917, “Woman Arrested as Smuggler of Opium,” again referring to Florence Loftus’s work for the Customs Service—this time, her activities seem more in line with the original role as envisioned in the 1866 congressional act. According to the Seattle Times story, the arrested woman was “turned over to Mrs. Loftus, wife of Chief Inspector Frank P. Loftus, to be searched.”

Finally, in 1920, two articles published in the Seattle Daily Times mention Florence Loftus in her professional capacity. The first, from 1 November, is headlined "Women Smugglers to Receive More Attention." According to the Times story, "Miss Alice R. Lyons," has been newly appointed as an inspector in the Customs Service in Seattle. Her "duties will be to search all women who are suspected of trying to bring in narcotics, liquor or contraband merchandise, and to supervise all feminine passengers arriving in Seattle.” As a new female inspector, she “will work with Mrs. F. P. Loftus, the only other woman inspector now in the customs service in this state.”

A second, longer article about the new hiring in the Customs Office appears in the Seattle Daily Times a few days later, on 7 November, “Women Bootleggers Out of Luck; Woman Customs Officer Named.” What’s interesting here is that the story focuses not on Florence Loftus, who has been working some 10 years by this point, but on Alice Lyons, who is only 21 years old. The article states that “Mrs. F. P. Loftus” has “myriad other duties” that seem to keep her so busy that they “preclude a close watch over women bringing proof of their visits to other countries,” so the hiring of a second female inspector has been made. I wish there was more about Florence Loftus's "myriad other duties."

And that's all I've been able to discover about Florence Loftus's career as a Customs inspector. She does appear several times in the Official Register of the United States Containing a List of the Officers of the Civil, Military and Naval Services, but these volumes only contain her job title and her salary. (Click here for the register from 1919, for example.)

The two Seattle papers do contain many more references to the activities of "Mrs. Frank P. Loftus," but these are all in the society columns--tea parties and card parties and costume parties and dinner parties and trips to and fro. They show her involvement with a number of local charities and with many friends, but they reveal little about the inner woman, the kinds of things I'd like to know: why she began working with the Customs Service, what her daily work routine was like, how she saw her role in the Customs Service, and how--or whether--her work was important to her. Was she treated well by her male colleagues? Did they value her contributions to the service? Did they resent her, as the wife of the chief inspector?

What followed for me, in the next few days, was a long and increasingly single-minded search to track down Florence Loftus on various genealogy sites. I could find a bit more about her, but not much. She first appears as "Flora B. Summers" in the 1880 U.S. Census, when she and her brother, Harry, are living in the home of their grandparents, Abraham and Susanna Summers. She is said to be 9 years old, which would put the year of her birth about 1870 or 1871.

There is no clue about who her parents are--the only reference I could find to her father was on her death certificate, where he is said to be "Frank Sommers [sic]." But no online family history information indicates that Abraham and Sarah had a son named Frank, nor have I been able to track down any man by that name whose details--age, birthplace, marital status, residence, children--conform to those provided in various U.S. Census records where information about Florence's parents is recorded. In the 1880 census, Florence's grandfather reports that her father was born in Ohio. This is the same information Florence herself provides in the 1900 census, but by 1910 she is reporting that her father was born in Pennsylvania. In subsequent years, she goes back and forth in reporting these various places for her father's birth. About her mother, the records are also silent, except that she was born in Scotland. Or Nebraska. Florence's accounts vary.

Despite all the genealogical information available online, I still can't even be sure about Florence's date of birth. I can't find a record of her birth anywhere. In 1880, her grandfather says she is 9 years old, making the year of her birth about 1870 or 1871, as I said. But when Florence herself is reporting the year of her birth, it varies wildly--in the 1900 census, the first where she is providing the information for herself, she does say that she was born in 1870 (in March of that year, to be precise). So far, this confirms her grandfather's information. But after that, there is nothing but confusion: in 1910, she claims to be 34 years old, which would make her birth in 1876; in the 1920 census, she claims to be 38, which would make her year of birth 1882; in the 1930 census, she claims to be 50, which would make her year of birth 1880; according to her death certificate, Florence was born on 17 October 1876—her age is recorded as 63 years, 1 month, and 4 days. Does this solve the question about her year of birth definitively?

Aside from these inconsistencies, Florence and her husband also have trouble remembering the date of their marriage. A society note in the 12 August 1889 Seattle Daily Times reports the arrival of "Mr. and Mrs. Frank P. Loftus" in Seattle in order to attend a "camping party." But, oops, the couple's marriage certificate shows that they weren't married until a month later: on 12 September 1889, Florence Summers, of Pierce County, Territory of Washington, marries Frank P. Loftus, of Jefferson County, Territory of Washington, in St. Leo’s Church, Tacoma, Territory of Washington.

But even with a marriage certificate, these two can't seem to remember when they were married. In the 1900 census, they report that they've been married 10 years, which would be about right, but in the 1910 census, they report they have been married for 15 years. The 1930 census, instead of asking how long a person has been married, asks for age at “first marriage,” which Frank lists as 28 and Florence as 16—if he was born in 1861 (which is what his death certificate says), that would mean Frank married for the first time about the year 1889 which is, in fact, the date on the marriage certificate. If Florence is 50 years old, as she claims in this census, this would mean she married for the first time in 1896 . . . If she were born in 1870 or 1871, as her grandfather reported (and she claimed in 1900), her first marriage would have been about 1886, but if she were born in 1876, as she also reports, her marriage would have been about 1892.

As you can tell, I've spent a lot of time trying to track down and sort through details about Florence Loftus's life. The difficulties she has with dates--her date of birth and her marriage, specifically--have become something of an obsession, and I have tried to figure out whether both she and Frank are simply careless with dates or whether there is some reason for the confusion. All I can say for sure is that if (a big "if") she were born in 1876, as her death certificate indicates, she would have been 13 years old when she married Frank (age 28) in 1889--and maybe some discomfort about that early marriage is the reason behind the discrepancies. Or maybe not--who knows? I have had weeks now to concoct all kinds of fanciful stories and scandals, but the simplest explanation is probably that dates weren't really important to them.

And there is no information at all about how Florence B. Summers made her way from Ohio, where she was living with her grandparents in 1880, to California, and then to Washington, where she was married in 1889 to Frank Loftus, who himself came from California. She probably traveled west with her brother, Harry, since his wife (and later, widow) spends time with Florence and Frank in Seattle, and Harry seems to have resided in California and/or in Port Townsend, Washington (accounts vary). According to that 1880 census, the one where Florence and her brother were living with their grandparents, Harry was just a year or two older than his sister. If they traveled west as teenagers, did they travel alone? Who or what were they hoping to find in California? Why did they decide to move on to Washington?

So personal information about Florence Loftus remains almost as elusive as details about her role as a Customs inspector. The most personal details of Florence's professional life are revealed when her husband commits suicide on 7 November 1937. I found the death certificate of Frank Loftus well after midnight one night, and I was shocked. I'd become so invested in Frank and Florence that when I saw his cause of death--"Right temple gunshot wound, Suicide, self-inflicted, home"--I found it unexpectedly upsetting.

I went back to the digitized archive of Seattle newspapers--I'd stopped searching them when Frank Loftus retired from the Customs Service in 1932. I had read a couple of articles about his retirement, then turned back to searching for genealogical information about Florence. But as I searched now, I found that both Seattle papers had printed big articles on the suicide of Frank Loftus, the storied Chief Inspector whose amazing exploits had filled so many column inches in the decades of his service. The front-page story in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer was particularly lurid ("Maddened by pain from which medical science was unable to offer him any relief," he had "found his peace in his own way" by shooting himself "through the head in his home").

The accounts of this terrible tragedy allow us--perhaps--to hear the voice of Florence Loftus. In the Times account of Loftus's death: "He has been suffering for more than two years," Florence is reported to have said, "But to have him go so suddenly leaves me almost stunned. He always has been so cheerful" ("Frank P. Loftus Ends Own Life," Seattle Daily Times,8 November 1937, p. 19).

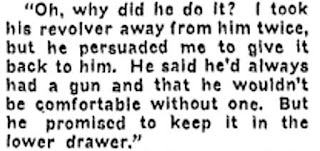

The P-I quotes Florence as well, but in keeping with its more sensational account of Frank Loftus's suicide, the scene is melodramatic. Informed of her husband's death, Florence reportedly asks, "He--he didn't shoot himself, did he?" And then, when her fears are confirmed, she "wailed." From the article:

|

| "Frank Loftus, Ex-Customs Aid, Suicide, Suffering Leads Invalid to Take Life," Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 8 November 1937, p. 1 |

I say we can "perhaps" hear Florence's own voice, because although her words are put in quotation marks in these stories, we can’t be sure they are her words--"her" voice is ventriloquized through the newspaper reporters as well as through those who who broke the news of her husband’s death to her. We only "hear" her voice indirectly, transmitted by someone who spoke to her and conveyed "her" words to a reporter, who then included them in the article on Frank's death printed in the paper. They may be her words. Or maybe the news writer made them up. Who can be sure?

But there are a couple of details in these accounts of Frank Loftus's suicide that do give us a bit of insight into Florence Loftus's professional life. First, she was "on duty" when her husband killed himself. Although Frank Loftus had retired 5 years earlier, in 1932, Florence clearly continued to work. She was "at the Great Northern dock, meeting a Japanese ship" when news of her husband's death was given to her. And second, she would continue at the Customs Service. The day after her husband's suicide, in fact, the Seattle Daily Times reports, "Today his bereaved widow prepared to return to her work as a customs inspector." She would work for some time after her husband's death.

Although I am still unclear about when Florence Summers Loftus was born, she died two years after her husband, on 21 November 1939. I was gratified to find that both Seattle papers published obituaries--each one noting her independent career as a U.S. Customs Inspector, not relegating her life to her role as the wife of a chief inspector of the Customs Service.

In the Seattle Daily Times, her death was noted in the "Obituaries" column:

In the Post-Intelligencer, a small article noted her death:

And so here she is, Florence B. Summers Loftus, lost and found. An extraordinary "ordinary" life.

One final note: I've spent weeks tracking down everything I could find out about Florence Loftus, her family, her movement from Nebraska to Ohio to California to Washington, her career in the Customs Service from 1909 to 1937.

I know that she and her husband bought a Great Majestic Range in 1904, I know that she contributed to a Christmas charity fund in 1912, I know that she won "first prize" at a "guessing party" she attended in 1924.

But I still don't know what the "B" in her name stands for . . .

*Of course, given the current regime's focus on disappearing history, this link now takes you to a "we're sorry, we fucking removed this woman from our website" notice. You can still click a "History" link, and there is still a "Did you know?" link, but the information about Anna C. M. Tillinghast has been scrubbed. Here is the rather lengthy essay about her, in the page preserved by the Internet Archive before the 2026 scrubbing--click here.

**This is now gone as well--as of 19 February 2026, the link takes you to an online betting site. Here's the history timeline, as preserved by the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine: click here.