When Women Became No Longer Equal, Part 8: Time for Deeds, Not Words?

An improbable confluence of events has gotten me thinking about the motto of one of the twentieth century suffragist organizations: "Deeds, not words."

Last Friday, 15 July 2022, was anniversary of the birth of the militant political activist

Emmeline Pankhurst--Pankhurst founded the Women's Social and Political Union, the organization that adopted that motto. "Deeds, not words" were needed, she said.

And on that same day, Friday, 15 July 2022, the U. S. House of Representatives passed two bills, neither of which has a chance in hell of passing in the Senate. The first,

H.R.8297, Ensuring Access to Abortion Act of 2022, would guarantee that a woman had the right to travel freely wherever she chose and for whatever reason she chose--specifically, that no state could prevent a woman from crossing state lines to get an abortion. The second,

H.R.8296, Women’s Health Protection Act of 2022, would prohibit "governmental restrictions on the provision of, and access to, abortion services."

Even though the House passed both bills, the final votes were grim. The first act, ensuring a woman's right to free movement, passed by a

vote of 223 to 205--only three Republicans thought a woman should be able to travel out of state if she made the decision to do so for reasons that were nobody else's business. The second passed by a

vote of 219 to 210, no Republicans agreeing that a woman was entitled to self-determination and bodily autonomy. (The final tally is different on these two votes because not everyone voted.)

So, as I said, the startling meeting of these two things on this one day got me thinking. Is now the time for women in America to consider "deeds, not words"?

A bit of history. Emmeline Pankhurst had been active in the effort to gain the vote for women for decades. Beginning in

the early nineteenth-century, women had marched and had held rallies and had displayed banners and had spoken at public meetings and had published pamphlets and books and had petitioned and had drafted and redrafted legislation. And they had seen three successive suffrage bills--1870, 1886, and 1897--fail

In 1903, disillusioned with established suffrage organizations and tired of the parliamentary promises that failed to result in action, Pankhurst and a group of like-minded women founded the Women's Social and Political Union--a militant group whose activities soon moved from non-violent to violent, a group whose chosen motto was "deeds, not words."

These women, women who were sick to death of being ignored, were militant but peaceful at first, and their movement grew--the WSPU organized a "Women's Sunday" rally at Hyde Park in June 1908 that drew a crowd of 250,000 people. But, finding their protests and issues ignored, women turned to smashing windows in Downing Street and fastened themselves to railings. Their demonstrations grew increasingly violent, perhaps none more so than the

Black Friday protests on 10 November 1910, following parliament's failure--once again--to pass a suffrage law that would have granted at least

some women, property-owning women, the right to vote.

Members of the WSPU began a

campaign of violent actions--sure, they spit at politicians and threatened Winston Churchill with a horsewhip and heckled members of parliament. But they also broke windows,

slashed paintings, blew up mailboxes, committed arson, cut telegraph wires, and planted bombs. And they were not apologetic.

In 1913, Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pankhurst's daughter, felt

no need to excuse the tactics of the WSPU: "If men use explosives and bombs for their own purpose they call it war, and the throwing of a bomb that destroys other people is then described as a glorious and heroic deed. Why should a woman not make use of the same weapons as men. It is not only war we have declared. We are fighting for a revolution!"

Meanwhile, Emmeline Pankhurst traveled to the United States, where she addressed her speech, "Freedom or Death," to an audience in Hartford. Connecticut on 13 November 1913.

Pankhurst' speech is long--I'll link you here to the

speech in its entirety. But so much of it seems relevant to this current moment and the alarming future that women in the United States face as their rights to self-determination and bodily autonomy have been erased by the Supreme Court, and where multiple states are resorting to other drastic measures, including the right of women to travel freely.

In opening her address, Pankhurst says, "I am not here to advocate woman suffrage." Rather than an advocate, she asserts, "I am here as a soldier, one who has temporarily left the field of battle in order to explain--it seems strange it should have to be explained--what civil war is like when civil war is waged by women."

from Emmeline Pankhurst's "Freedom or Death"

I am not only here as a soldier temporarily absent from the field at battle; I am here--and that, I think, is the strangest part of my coming--I am here as a person who, according to the law courts of my country, it has been decided, is of no value to the community at all: and I am adjudged because of my life to be a dangerous person, under sentence of penal servitude in a convict prison. So you see there is some special interest in hearing so unusual a person address you. I dare say, in the minds of many of you--you will perhaps forgive me this personal touch--that I do not look either very like a soldier or very like a convict, and yet I am both.

Now, first of all I want to make you understand the inevitableness of revolution and civil war, even on the part of women, when you reach a certain stage in the development of a community's life. It is not at all difficult if revolutionaries come to you from Russia, if they come to you from China, or from any other part of the world, if they are men, to make you understand revolution in five minutes, every man and every woman to understand revolutionary methods when they are adopted by men.

Many of you have expressed sympathy, probably even practical sympathy, with [such] revolutionaries. . . . It is quite easy for you to understand--it would not be necessary for me to enter into explanations at all--the desirability of revolution if I were a man. . . . If an Irish revolutionary had addressed this meeting . . . it would not be necessary for that revolutionary to explain the need of revolution beyond saying that the people of his country were denied--and by people, meaning men--were denied the right of self-government. That would explain the whole situation. If I were a man and I said to you, "I come from a country which professes to have representative institutions and yet denies me, a taxpayer, an inhabitant of the country, representative rights," you would at once understand that that human being, being a man, was justified in the adoption of revolutionary methods to get representative institutions. But since I am a woman it is necessary in the twentieth century to explain why women have adopted revolutionary methods in order to win the rights of citizenship.

You see, . . . we women, in trying to make our case clear, always have to make as part of our argument, and urge upon men in our audience the fact--a very simple fact--that women are human beings. It is quite evident you do not all realize we are human beings or it would not be necessary to argue with you that women may, suffering from intolerable injustice, be driven to adopt revolutionary methods. We have, first of all to convince you we are human beings [emphasis added]. . . .

I am going to talk later on about the grievances, but I want to first of all make you understand that this civil war carried on by women is not the hysterical manifestation which you thought it was, but was carefully and logically thought out, and I think when I have finished you will say, admitted the grievance, admitted the strength of the cause, that we could not do anything else, that there was no other way, that we had either to submit to intolerable injustice and let the woman's movement go back and remain in a worse position than it was before we began, or we had to go on with these methods until victory was secured; and I want also to convince you that these methods are going to win, because when you adopt the methods of revolution there are two justifications which I feel are necessary or to be desired. The first is, that you have good cause for adopting your methods in the beginning, and secondly that you have adopted methods which when pursued with sufficient courage and determination are bound, in the long run, to win.

We found that all the fine phrases about freedom and liberty were entirely for male consumption, and that they did not in any way apply to women. [emphasis added] When it was said taxation without representation is tyranny, . . . everybody quite calmly accepted the fact that women had to pay taxes and even were sent to prison if they failed to pay them--quite right. We found that "Government of the people, by the people and for the people" . . . was again only for male consumption; half of the people were entirely ignored; it was the duty of women to pay their taxes and obey the laws and look as pleasant as they could under the circumstances. In fact, every principle of liberty enunciated in any civilized country on earth, with very few exceptions, was intended entirely for men, and when women tried to force the putting into practice of these principles, for women, then they discovered they had come into a very, very unpleasant situation indeed.

Now, I am going to. . . come right up to the time when our militancy became real militancy, when we organized ourselves on an army basis, when we determined, if necessary, to fight for our rights just as our forefathers had fought for their rights. Then people began to say that while they believed they had no criticism of militancy, as militancy, while they thought it was quite justifiable for people to revolt against intolerable injustice, it was absurd and ridiculous for women to attempt it because women could not succeed. After all the most practical criticism of our militancy coming from men has been the argument that it could not succeed. They would say, "We would be with you if you could succeed but it is absurd for women who are the weaker sex, for women who have not got the control of any large interests, for women who have got very little money, who have peculiar duties as women, which handicaps them extremely--for example, the duty of caring for children--it is absurd for women to think they can ever win their rights by fighting; you had far better give it up and submit because there it is, you have always been subject and you always will be." Well now, that really became the testing time. Then we women determined to show the world, that women, handicapped as women are, can still fight and can still win. . . .

You have to make more noise than anybody else, you have to make yourself more obtrusive than anybody else, you have to fill all the papers more than anybody else, in fact you have to be there all the time and see that they do not snow you under, if you are really going to get your reform realized.

That is what we women have been doing, and in the course of our desperate struggle we have had to make a great many people very uncomfortable. . . . [I]f you really want to get anything done, it is not so much a matter of whether you alienate sympathy; sympathy is a very unsatisfactory thing if it is not practical sympathy. It does not matter to the practical suffragist whether she alienates sympathy that was never of any use to her. What she wants is to get something practical done, and whether it is done out of sympathy or whether it is done out of fear, or whether it is done because you want to be comfortable again and not be worried in this way, doesn't particularly matter so long as you get it. We had enough of sympathy for fifty years; it never brought us anything, and we would rather have an angry man going to the government and saying, my business is interfered with and I won't submit to its being interfered with any longer because you won't give women the vote, than to have a gentleman come onto our platforms year in and year out and talk about his ardent sympathy with woman suffrage. . . .

Very well, then when you have warfare things happen; people suffer; the noncombatants suffer as well as the combatants. And so it happens in civil war. When your forefathers threw the tea into Boston harbor, a good many women had to go without their tea. It has always seemed to me an extraordinary thing that you did not follow it up by throwing the whiskey overboard; you sacrificed the women; and there is a good deal of warfare for which men take a great deal of glorification which has involved more practical sacrifice on women than it has on any man. It always has been so. The grievances of those who have got power, the influence of those who have got power commands a great deal of attention; but the wrongs and the grievances of those people who have no power at all are apt to be absolutely ignored. That is the history of humanity right from the beginning.

They have said to us government rests upon force, the women haven't force so they must submit. Well, we are showing them that government does not rest upon force at all: it rests upon consent. As long as women consent to be unjustly governed, they can be, but directly women say: "We withhold our consent, we will not be governed any longer so long as that government is unjust." Not by the forces of civil war can you govern the very weakest woman. You can kill that woman, but she escapes you then; you cannot govern her. And that is, I think, a most valuable demonstration we have been making to the world. We have been proving in our own person that government does not rest upon force; it rests upon consent; as long as people consent to government, it is perfectly easy to govern, but directly they refuse then no power on earth can govern a human being, however feeble, who withholds his or her consent. . . .

When they put us in prison at first, simply for taking petitions, we submitted; we allowed them to dress us in prison clothes; we allowed them to put us in solitary confinement; we allowed them to treat us as ordinary criminals, and put us amongst the most degraded of those criminals: and we were very glad of the experience, because out of that experience we learned of the need for prison reform; we learned of the fearful mistakes that men of all nations have made when it is a question of dealing with human beings; we learned of some of the appalling evils of our so-called civilization that we could not have learned in any other way except by going through the police courts of our country, in the prison vans that take you up to prison and right through that prison experience. It was valuable experience, and we were glad to get it. But there came a time when we said: "It is unjust to send political agitators to prison in this way for merely asking for justice, and we will not submit any longer."

It has come to a battle between the women and the government as to who shall yield first, whether they will yield . . . , or whether we will give up our agitation.

Well, they little know what women are. Women are very slow to rouse, but once they are aroused, once they are determined, nothing on earth and nothing in heaven will make women give way; it is impossible. [emphasis added]

Now, I want to say to you who think women cannot succeed, . . . what would you say if in your state you were faced with that alternative, that you must either kill them or give them their citizenship--women, many of whom you respect, women whom you know have lived useful lives, women whom you know, even If you do not know them personally, are animated with the highest motives, women who are in pursuit of liberty and the power to do useful public service? Well, there is only one answer to that alternative; there is only one way out of it, unless you are prepared to put back civilization two or three generations: you must give those women the vote. Now that is the outcome of our civil war.

. . . You have left it to women in your land, the men of all civilized countries have left it to women, to work out their own salvation. . . . [W]e will put the enemy in the position where they will have to choose between giving us freedom or giving us death.

. . . Even the most hardened politician will hesitate to take upon himself directly the responsibility of sacrificing the lives of women of undoubted honor, of undoubted earnestness of purpose. That is the political situation as I lay it before you today. . . .

We have to look facts in the face. [W]omen have learned to look facts in the face; they have got rid of sentimentalities; they are looking at actual facts: and when [men] talk about chivalry, and when they talk about putting women on pedestals and guarding them from all the difficulties and dangers of life, we look to the facts in life as we see them and we say: "Women have every reason to distrust that kind of thing, every reason to be dissatisfied; we want to know the truth however bad it is, and we face that truth because it is only through knowing the truth that you ever will get to anything better." We are determined to have these things faced and cleared up, and it is absolutely ridiculous to say to women that they can safely trust their interests in the hands of men who have already registered in the legislation of their country a standard of morals so unequal for both sexes. . . .

Well, can you wonder that all these things make us more militant? It seems to me that once you look at things from the woman's point of view, once you cease to listen to politicians, once you cease to allow yourself to look at the facts of life through men's spectacles but look at them through your own, every day that passes you are having fresh illustrations of the need there is for women to refuse to wait any longer for their enfranchisement. . . .

Men have done splendid things in this world; they have made great achievements in engineering; they have done splendid organization work; but they have failed, they have miserably failed, when it has come to dealing with the lives of human beings. They stand self-confessed failures, because the problems that perplex civilization are absolutely appalling today. Well, that is the function of women in life: it is our business to care for human beings, and we are determined that we must come without delay to the saving of the race. The race must be saved, and it can only be saved through the emancipation of women. [emphasis added]

Well, ladies and gentlemen, I want to say that I am very thankful to you for listening to me here tonight; I am glad if I have been able even to a small extent to explain to you something of the English situation. I want to say that I am not here to apologize. I do not care very much even whether you really understand, because when you are in a fighting movement, a movement which every fiber of your being has forced you to enter, it is not the approval of other human beings that you want; you are so concentrated on your object that you mean to achieve that object even if the whole world was up in arms against you. So I am not here tonight to apologize or to win very much your approbation. People have said: "Why does Mrs. Pankhurst come to America? Has she come to America to rouse American women to be militant?" No, I have not come to America to arouse American women to be militant. I believe that American women . . . will find out for themselves the best way to secure that object. . . .

So here am I. I come in the intervals of prison appearance: I come after having been four times imprisoned . . . , probably going back to be rearrested as soon as I set my foot on British soil. I come to ask you to help to win this fight. If we win it, this hardest of all fights, then, to be sure, in the future it is going to be made easier for women all over the world to win their fight when their time comes. So I make no apologies for coming. . . .

Of course, Pankhurst was arguing for women's suffrage. And women finally did get that right--no small thanks to their "deeds." In both Britain and the United States, women's militancy before the First World War ensured they got the vote after its end.

And it's important to remember--the right to vote was

not a right that they were

given, a reward for their agreeableness and good behavior. As

Eleanor Smeal, president of the Feminist Majority, notes, "The textbooks when I went to school said women were given the vote." But nothing could be farther from the truth: "We weren’t given anything. We took it."

Today, in the face of women's outrage and despair, as they are being told that, sorry, they are not quite equal after all, sanctimonious judges and politicians are also telling them that if they aren't happy, they just need to vote for change. Why are you so upset, they ask. After all, we gave you the right to vote, so just go vote.

Just vote, and everything will be fine. But in the light of the gutting of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, of undisguised and calculated efforts at voter suppression and years of partisan gerrymandering, and after years of packing and stacking the federal courts at all levels with right-wing religious zealots--well, in light of all of this, will voting do it?

As Smeal reminds us--women weren't been given anything. They had to take their rights from those who determined to deny them.

And as Emmeline Pankhurst reminds us--to be regarded as equal under the law, to be treated as human beings, women may need to become revolutionaries.

|

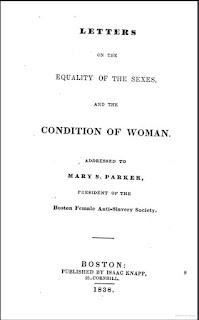

Women protesting outside the U.S. Supreme Court

following the Dobbs decision,

AP Photo |

Update, 21 July 2022: They're coming for for us, now doing everything they can to reduce a woman--an independent, autonomous person--to the status of a

vessel, a receptacle, a sort of Tupperware container, just ready and waiting for some guy to deposit his semen. Today, the U.S. House of Representatives considered

H.R.8373, To Protect a "Person’s Ability to Access Contraceptives and to Engage in Contraception, and to Protect a Health Care Provider’s Ability to Provide Contraceptives, Contraception, and Information Related to Contraception."

Yes, this bill would ensure a person--a human being--would be able to make informed decisions about whether and when she will become pregnant. It would also ensure a person had access to information about birth control.

Only 8 Republicans thought women should be assured such access--220 Representatives

voted in favor of H.R. 8373, but only 8 of them were Republicans. The vast majority of Republicans--195--

voted against this bill. (Two Republican weenies voted "present," while eight lacked enough conviction to vote at all. I mean, if you're a benighted, misogynist asshole, at least have the courage of your convictions . . .

And good luck getting this through the Senate . . .